Internet Everywhere

Comments on an old Art Forum article from Claire Bishop entitled “DIGITAL DIVIDE: CONTEMPORARY ART AND NEW MEDIA”

Digitalization didn’t happen the way we thought it would. The declaration of independence of cyberspace, the idea that everything will become virtual in the future, this was a projection into the future based on the stationary personal computer experience. Even critics of the disembodiment of digital technologies were wrong, such as Bourriaud that, as Claire points out in her essay, postulated relational aesthetics as a preference for face-to-face meetings over the disembodiment of the internet.

Today, you hear this kind of talk mostly coming out of the copyright industry that only a few years ago feared everything digital. But the success of their lobbying and social media consultants have now turned them into the avant-garde of digitalization, hoping to sell something that cost nothing to people who already have it.

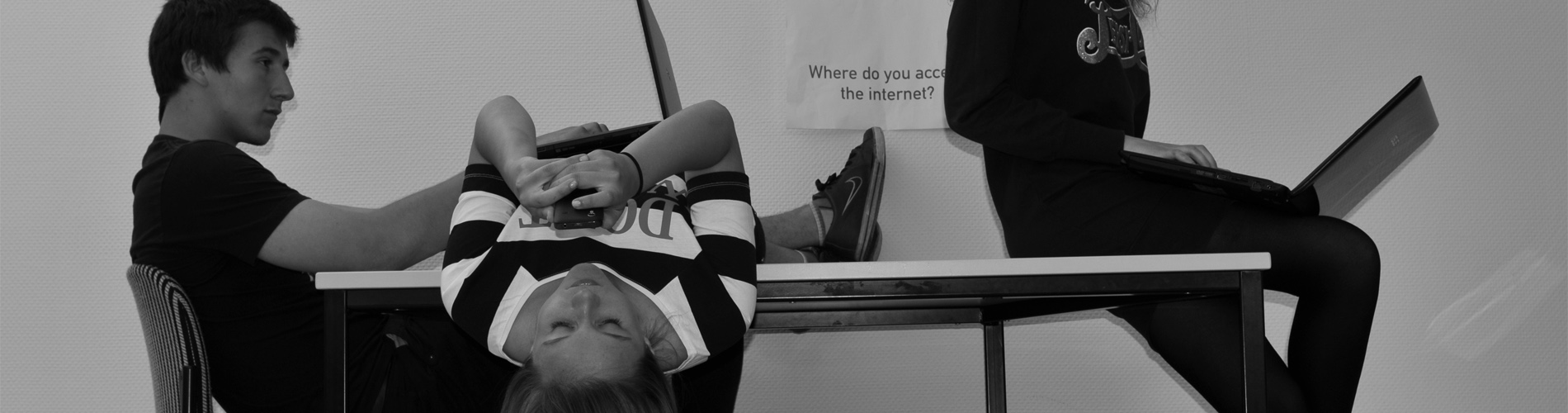

We didn’t end up spending all the time on the internet, but with the internet. Everything didn’t move to the internet, the internet moved everywhere. Everything is embedded with networking and computational abilities, which makes everything a little bit weird.

That’s why I think the artist fascination with second life was such a misdirection. Some people did went that way. The World of Warcraft people. And boy, did they just disappear over night.

But the rest instead went on to create a very tight (low data consuming) interface between the internet and the time-space of their lives. This is what created the eerie oscillation between intimacy and distance that Claire Bishop talks about in “Digital Divide”.

This relation is talked about in The Cybernetic Hypothesis released by Tiqquin in 2001 [@tiqqun:2001hypothèse] Here they talk about how the cybernetic hypothesis, as the dominant form of power today, first needs to destroy all social bonds, only to reconnect them on its own systemic terms. This of course echoes Marx description of capitalism that destroys all feudal social bonds only to reconnect people through the wage- and commodity-relation.

And this dis- and re-connection of cybernetics have since WWII been seen as both a liberating and an oppressing force. As Fred Turner describes in his book “From Counter-culture to Cyber-culture” [@turner:2006from] computers went in just barely two decades from being seen as instruments of the cold war and american state and corporate bureaucracy to being tools for personal liberation. And still today I think we are fighting this inner conflict of whether cybernetics and systems will liberate is or dominate us on new ways.

What I like about the Cybernetic Hypothesis is that is postulates powers as something interactive. Like Claire says, we don’t live anymore in the spectacle world as Guy Debord envisioned it – that’s a mass media world – but in a world dominated by “a language of platforms, collaborations, activated spectatorship, and “prosumers” who coproduce content”

Claire asks, with Lev Manovich, can this interactive relation be the subject of an aesthetic? I think this is the same question as to ask if it can become a new form of power. If an aesthetic requires a situation to be shaped by an artist, however subtle, we are dealing with a new form of power. And this I think is highlighted in several works that FAT makes.

I am suggesting that the digital is, on a deep level, the shaping condition—even the structuring paradox—that determines artistic decisions to work with certain formats and media.

The digital is the Real that can’t be subsumed within the work, but none the less structures it, or in worst case is the thing that the artwork simply reacts against. With a reservation we can put the so called “hauntology” here. Hauntology is interesting because it is about remembering, but remembering wrong, that is subjectively, and therefor creating something new, for example remembering several time periods juxtaposed into one memory.

In relation to this the hacker attitude is so important. It basically does what media archeology does to the past, but with the present. Finds alternative potentials within what on the surface looks like a totally rigid system. That is if we still believe in the hacker. I’m not sure. Perhaps the hacker is destined to fail just a media archeology depicts a past that didn’t happen. Perhaps the hacker can show how the present could be, how we can do things differently, but in fact something else has already been chosen. A momentum is under way that has chosen something different. That’s why the pirate bay had to fail. It wasn’t possible to depart from the hack as the fixed point and suppose that the rest of society would revolve around this point. The hack gets crushed and at the same time those ideas are incorporated into institutionalized solutions.

More and more of the central infrastructure moves away from the reach of the hacker. Computer security is not the same as it used to be. Sure, its possible to hack email accounts and iPhones, but are those the systems that really control our world or are they simply left unsecured because they are not considered of vital importance? This is what I fear. That we can play around so much with consumer technology because power has moved elsewhere. You are only able to tweet because they have drones basically. This power relation is built into modern mobile phones where the user, even with a rooted device only has access to what amounts to a sandbox while the chip that controls the actually data and signal transmission is out of control.

Benjamin’s belief that the utopian potential of a medium may be unleashed at the very moment of its obsolescence.

But even digital devices are obsolete. The general purpose computer is obsolete for most consumers. Only specialists operate it nowadays, which in turn gives them incredible power.

What about the copy? This defining practice of the digital era. Everything you do on a computer involves copying. Simply reading a file consists of copying it from the hard drive into RAM memory. I think we need to distinguish between a pre-digital, modernist copy and the digital copy.

The modernist copy is the one that turns the known into the unknown, questions the established structure of the art system. It is best summed up by a question posed by Serbian artist Goran Djordjevic who once copied the entire armory show from MoMa while working as a doorman at the museum: “Is a copy of a Mondrian an abstract painting, or is it in fact a realist painting?” The modernist copy was about, as Claire says, “questioning authorship and originality while drawing attention, yet again, to the plight of the image in the age of mechanical reproduction.”

In the digital era, the copy has changed. As Claire says, “faced with the infinite resources of the Internet, selection has emerged as a key operation”. Issues of originality and authorship and upsetting order no longer concerns us. Instead, the question is how we create meaning from infinite abundance. We all have access to music collections bigger than what we ever would be able to listen to throughout our entire life-time. Claire again “Questions of originality and authorship are no longer the point; instead, the emphasis is on a meaningful recontextualization of existing artifacts.”

Although here something should be said about selection and meaning. The copyright industry, as I said, now the vanguard of digitalization, understands this on some level. They now launch services that gives a user infinite access to music or films for a subscription fee or similar. Streamable of course, therefor harder, but never impossible to copy. There is always the analog hole. They also invest a lot of effort into selection algorithms, building up user profiles of previous use and personal data and therefor having their algorithms recommend what other people with similar tastes have liked. But this is a mistake and forgets the essential social and communal foundation of meaning.

Therefor I think that the archival impulse somewhat is in vain. Even though I also obsessively archive text, music, video and friends as everyone else. This difference can perhaps be seen between twitter and IRC as modes of communication, with Twitter being archival, suggesting an ability to capture and organize all information. IRC being more about diving into a moment.

The question of new media creating its own structures versus getting recognition and being incorporated within dominant structures from a pre-digital era is highlighted also within the art world. Does new media artists create new structures, ways of working and perspectives on authorship and ownership? Yes. And in fact there are some inherit issues with fully integrating media art into the art system where it not only often lack a sellable object, to the extent on not really being able to do proper video documentation to in some cases not even having an author who can represent the work (which even disqualifies the media art festival circuit)! Do they also in the end rely of integration into the art system in other to become established and make a living as artists? Yes again. This is not a problem unique to the art world. Many of the early internets experimentation with anonymity and pseudonymity has been forced to be given up the more internet becomes tied to institutionalized social life, including institutionalized ways of making a living.